The Beginning of City Transportation Systems

The rise of city transportation is directly linked to the growth of cities in the 18th and 19th century. For example, in 1660 Dublin’s population was around 8,800 people, by 1760 it had grown to 141,000, and by 1860 there were over 260,000 inhabitants. As the population grew, the city spread out and absorbed smaller towns and villages, creating what we now call suburbs. Unless you were rich and had your own coach, you’d depend on renting a coach to travel around the city, and those weren’t exactly affordable either for the common man.

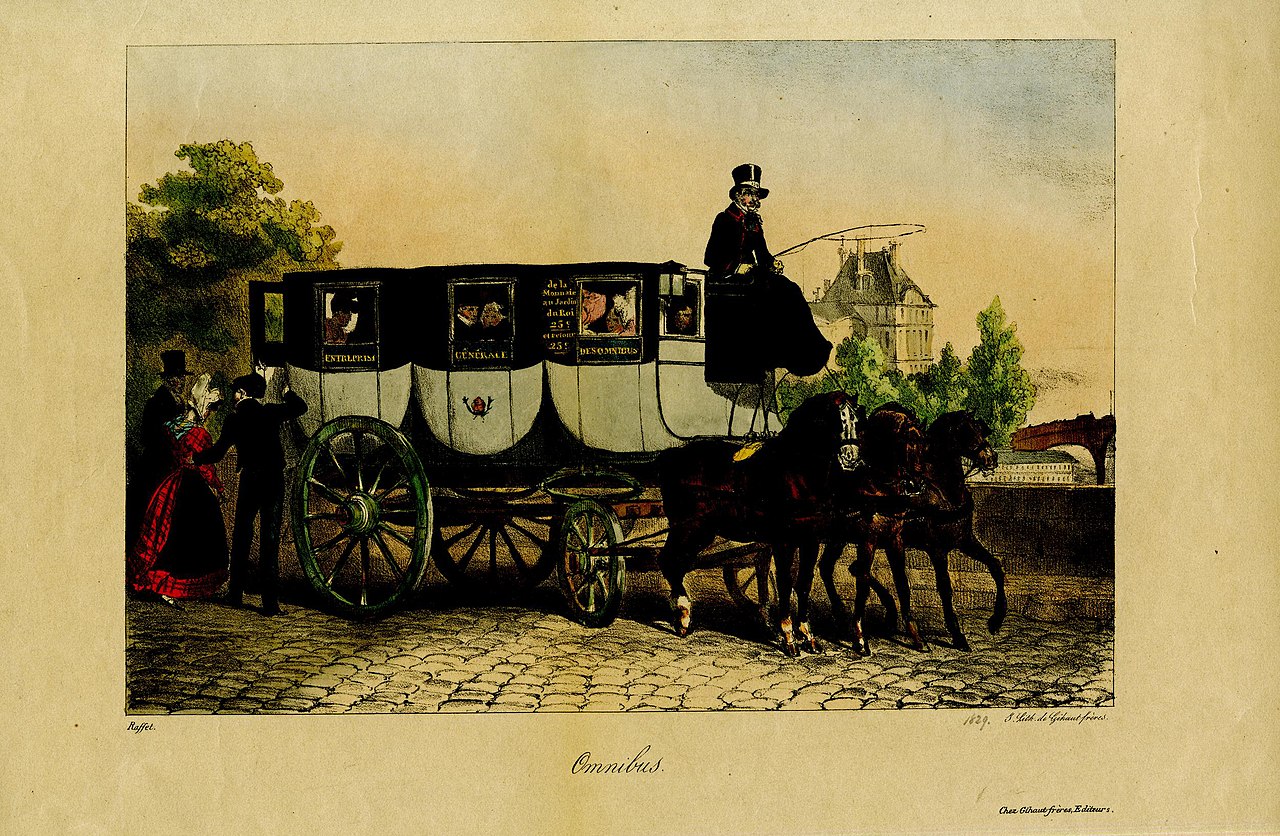

The idea of a coach transporting people along a fixed route within a city began in Nantes, France around 1823. A man called Stanislas Baudry opened a bath house far away from the city centre and started a shuttle service that left the town centre on a regular schedule. The first bus held 16 passengers, seated on two benches along the side of the coach.

After Baudry realised that not all passengers were going to the bath house, but used the shuttle to travel to destinations along the route, he saw an opportunity and opened up the first urban transit service in 1826 in Nantes, calling his coaches “Omnibus” (Latin for “for all”). He quickly expanded to Bordeaux, Lyon, and eventually Paris.

While Baudry’s business was very successful in the end, his own fate is rather tragic: he committed suicide after suffering a number of setbacks and a very bad business year in Paris. And the idea of the omnibus flourished and expanded throughout Europe. The first bus service starting in London in 1829 and Dublin in 1832. In Dublin, however, it ran into stiff opposition from the local coachmen who saw their business threatened, so it took two years before the first service was established.

The Start of the Trams

As long as the streets were smooth, these early busses were not too bad to ride. But on cobblestones the solid steel wheels would rattled the whole coach, and if the roads were muddy, it made it very hard on the horses to draw the much heavier carriages. Hilly locations often presented extra difficulties both needing extra horse power going up, and good brakes for the trip down. As the early busses in Europe mainly drove in the paved city centre areas, the development of what we would recognise as a tram service started in America where the streets were in much worse shape. So much so that a horse-drawn bus wasn’t really feasible sometimes.

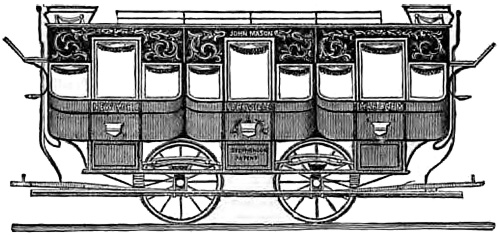

To counter those problems, an Irish coach builder called John Stephenson, who was living in New York, invented what we would now call a tram in 1932. The carriage looked more like a railroad carriage, with three separate compartments, and the wheels would run through rails which were laid in the street, resulting in a far smoother ride and less strain on the horses. It also allowed for the coaches to become bigger and carry more passengers.

First Dublin Trams

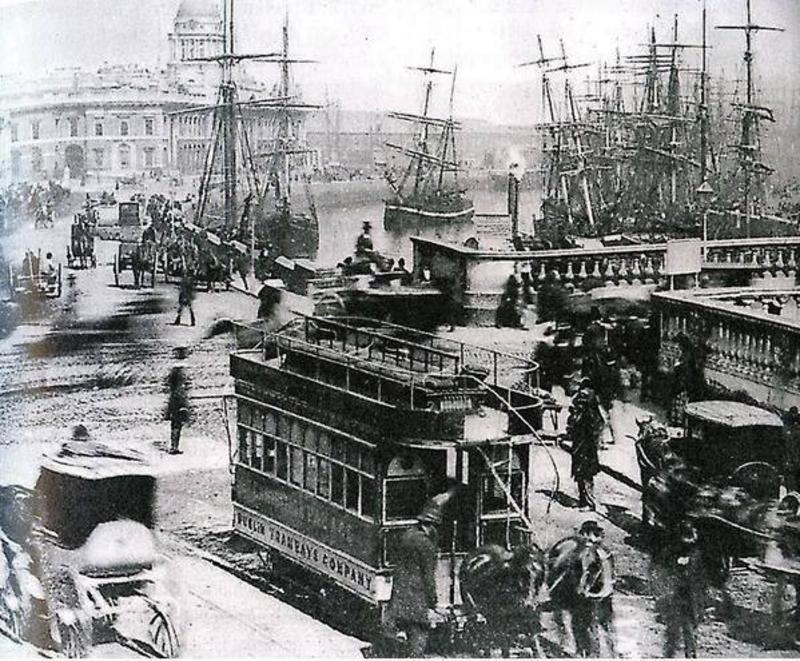

While John Stephenson and his trams were very successful in the USA and elsewhere in the world, it wouldn’t be until 1872 for the first tram line to appear in Dublin. The Dublin Tramways Company ran the first route from College Green to Rathgar and it was later extended in both directions to Nelson’s Pillar (now the Spire) and Terenure. The first trams in Dublin were double decker vehicles pulled by two horses. The double decker bus came about in 1847 and were widely in use at this point, and the trams adapted this design. The ladders leading to the upper deck were at the back and front of the vehicle, and the top was completely open. There were two long benches in the middle, facing sideways, and a metal railing running along the outside to stop people from falling over the edge.

The Irish Times was fairly hostile towards the whole idea, but had to admit:

As successors to the badly turned out antedeluvian omnibuses hitherto plying on this route, the Tramway carriages are an undoubted improvement if only in the desideratum of being properly lighted and properly driven at night.

Irish Times, February 1872

After the introduction, the lower part of the open deck railing was fairly quickly covered up with solid boards, called “Decency Boarding”, since they were intended to stop people on the street being able to peek up female passenger’s dresses. This boarding was of course also perfect for advertisements. The ladders were rather tricky to climb, especially going down, and they were relatively quickly replaced with a spiral staircase.

The Dublin Tramways Company opened up new tram lines very fast with several services already starting the very same year. The first of those opened in June and was a line called the “Three Stations” line which ran along the south quays, starting in what’s now Heuston Station, going to Harcourt Street Station (now a LUAS stop) and ending in what’s now called Pearse Station. The next opened in October and ran from Nelson’s Pillar to Sandymount via Bath Avenue. In 1873 lines were opened to Donnybrook, Dollymount, and a line running from O’Connell Bridge over the north Quays to Parkgate Street.

The Crew and Horses

At the height of the horse drawn tram network there were around 160 active trams, with another 20 or so that were under repair or being improved at any given time. Each tram was pulled by only two horses, but those were rotated out several times during the day to ensure they weren’t exhausted, which meant that the company owned around 10 horses for each tram. This also included a few trace horses that were roped in to help out with steep hills, and some extra capacity in case a horse fell sick. The horses were treated better than the men that worked on the trams. They had a veterinary surgeon looking after them, good quality stables, and they were well fed.

The staff on the other hand could be taken on and dismissed at will. All the rulebooks of the time list the duties and the company’s rights, but there was nothing in them about the rights of the staff regarding such things as lunch breaks, holidays, sick leave, etc. They were expected to work long days on the trams, exposed to the elements since the driver was standing out the outside, and had to bring their meals from home to have whenever they had a few minutes of free time during the day. They were also expected to advertise the tram as it was trotting along the street and call out to people walking “Car Sir?” or “Car Madam?” to persuade them to ride on the tram.

The Start of Competition and Experiments with New Technology

The success of the early lines, and DTC not constructing some of the lines they had proposed, opened up the way for competitors to enter the market. The North Dublin Street Tramways Company was the first, opening up lines to Phoenix Park, Glasnevin, and Drumcondra in 1875, and in 1878 the Dublin Central Tramways Co. joined the fray and opened up a line to Rathfarnham via Harold’s Cross. The last one to start that year was the Dublin Southern Districts Tramways Co. which ran a line from Haddington Road to Blackrock, and later from Dún Laoghaire to Dalkey.

That latter company also experimented with using steam locomotives instead of horses to pull the carriages on their lines between 1882 and 84. But the locals living along the route objected strongly, and the plan was abandoned with all trams reverting back to horse-drawn ones the next year.

The last of the smaller, independent horse tram companies was the Blackrock and Kingstown Tramways Co. (Kingstown being the old name for Dún Laoghaire), which connected Blackrock and Dún Laoghaire in 1883. This meant that you could now travel by tram from the city centre to Dalkey but would have to change trams twice and the travel time was over two hours. In comparison, the train would take 35 minutes, so the Dalkey line was never very profitable at this point.

Sources:

- Lecture by Michael Corcoran, at Dublin City Library and Archive on 23 January 2007.

- “Dublin Trams 1872-1959” by Francis J. Murphy, Dublin Historical Record, Vol. 33, No. 1 (Dec., 1979), pp. 2-9

- “‘Galleons of the Streets’: Irish Trams“; History Ireland, Issue 2 (summer 1997), volume 5

- The National Transport Museum website

- “Wonders and Curiosities of the Railway” by William Sloane Kennedy, 1884

- Dublin United Tramways article on Tramway Systems of the British Isles

Image Sources:

- Parisian Omnibus 1829 – Print made by: Auguste Raffet in 1829. From the collection of the British Museum.

- The John Mason 1832 – Print from “Wonders and Curiosities of the Railway” by William Sloane Kennedy, 1884

- First Dublin Tram 1872 – image obtained from Old Dublin Town website

- Custom House with Tram – image obtained from Old Dublin Town website

- Steam Engine used by the Dublin Southern Districts Tramways Co. – National Library of Ireland catalogue from the Science Museum, London.