(Part 1 – Beginnings, and Part 2 – Electrification and Unification can be found here, and there is also an addendum with other notable tram lines)

Expansion

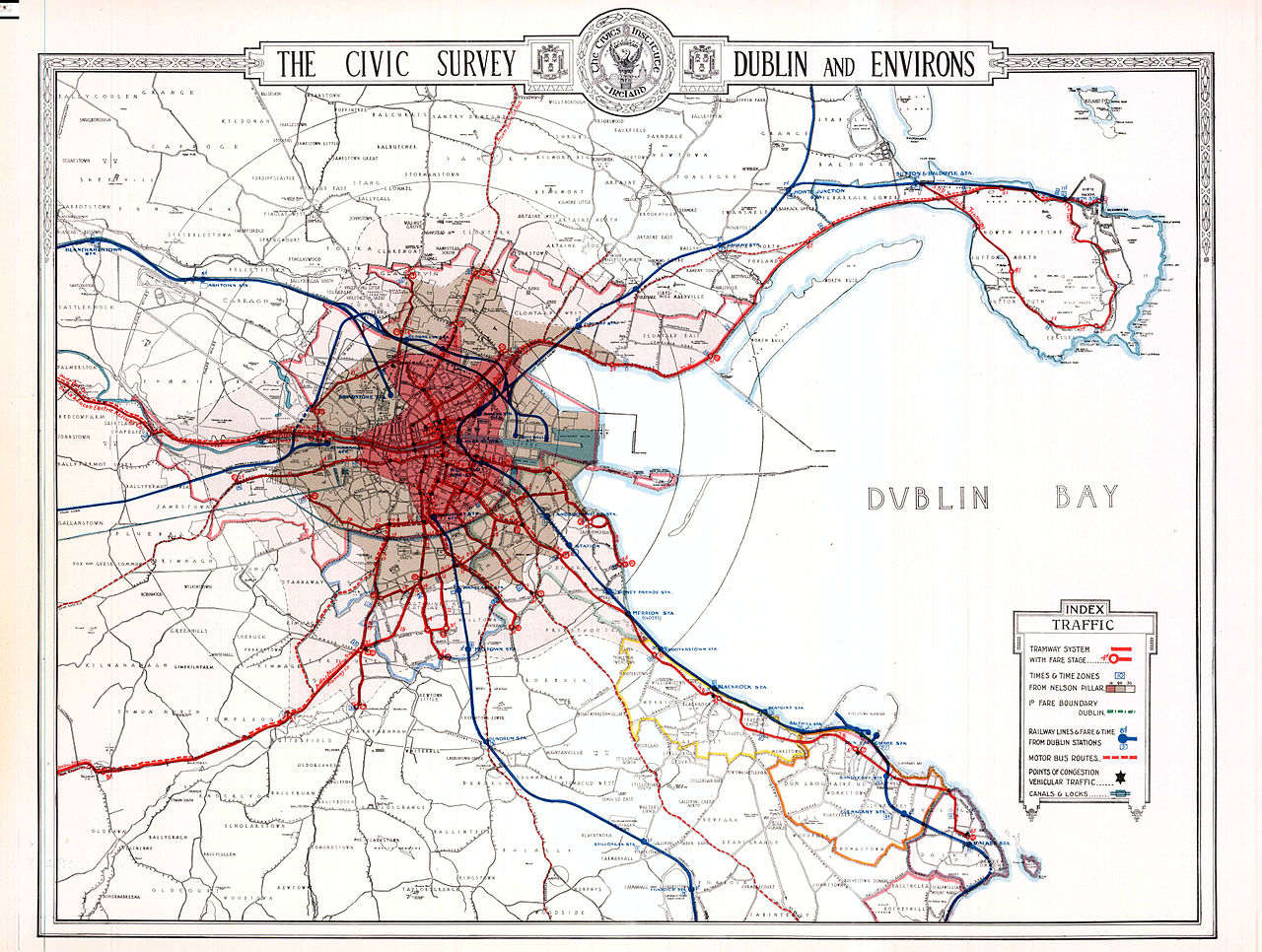

As well as rolling out electrification of the network in record speed, The new Dublin United Tramways Co. also expanded it. In 1899 a new route from Kenilworth Square to Lansdowne Road opened up, and a route from Clonskeagh to Nelson’s Pillar via Leeson Street. They also extended existing lines; Drumcondra was extended to Whitehall near Griffith Avenue, the Dolphin’s Barn route was extended to Rialto Bridge near St. James’ Hospital, and the Rathmines line to Dartry near the east side of current day Dartry Park.

The laying of track on Baggot Street in 1906 allowed the Donnybrook trams to run via St. Stephen’s Green And in the same year a large power station in Ringsend was completed which could power the whole network, leading to the closure of the two power stations in Clontarf and on Shelbourne road. The Art Deco style building that’s now used by Windmill Lane Studios used to be a DUTC power station as well, but this was built later in 1932, next to the larger, original power station from 1906.

Expansion of the network mostly stopped around 1913 though. First the Dublin Lock-out labour union dispute between the DUTC and the trade unions stopped any work for seven months. Then the outbreak of WWI forced the closure of some lines to preserve fuel for the war effort, and finally the War of Independence and following Civil War after the end of WWI damaged a lot of material and forced lines to close.

Logistics, Modernisation, and Creature Comforts

Over the years the DUTC made a number of changes how the trams themselves worked. The horse trams allowed people to hail them, and the tram would stop anywhere for the passengers to get on board or leave. But with the introduction of electric trams, the fixed stops we’re more familiar with today were introduced. Another change would be the colouring and how the destination was indicated. The horse trams were unique to each line. The vehicle had a specific colour and the destination was painted on the side, which means the cars weren’t interchangeable. The introduction of interchangeable destination boards in 1897 allowed cars to run on any route, and in 1904 those were replaced with the roller-blind system that was still in use on Dublin buses until the introduction of digital signs in the early 2000s.

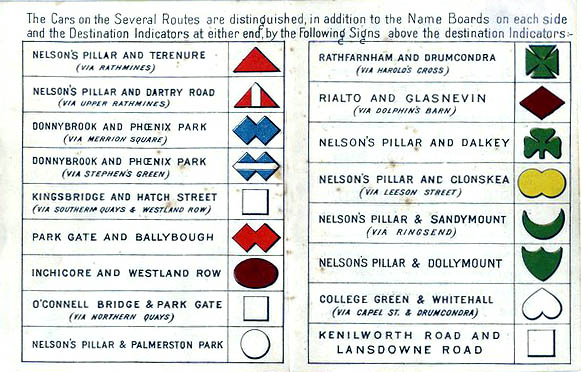

That year also saw the introduction of a symbol system for the routes to help people differentiate between the routes. At this point Sackville Street (now O’Connell Street) had become a hub of routes, and at least seven routes started at Nelson’s Pillar, and adding the symbols made it easier to pick the right tram. A night a combination of two coloured lights under the symbol were used.

The symbol system was replaced in 1918 by route numbers that are used for the buses till this day. The numbers were assigned in a clock-wise way, starting with route 1 to Ringsend and ending on 31 to Howth.

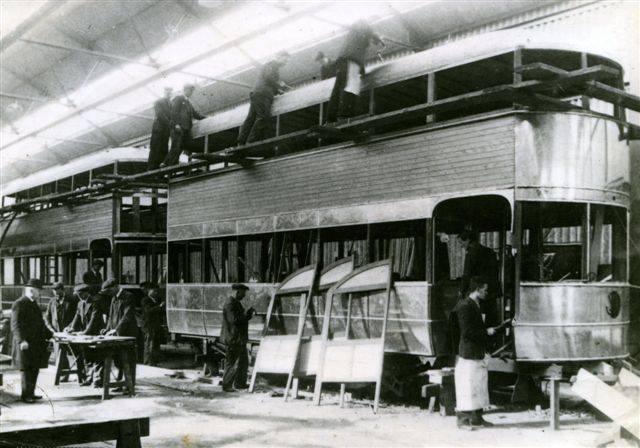

The trams were also improved over time. The driver and conductor finally received some protection from the elements with the first vestibuled cars appearing in 1898. And the top floor passengers started seeing fully roofed trams on some routes from 1904 onwards, although some routes remained open topped due to low railway bridges. In 1922 a new “Standard” car was introduced which was completely covered and had more comfortable seating.

The chairman of DUTC was a firm believer in producing all materials locally and from 1905 all trams used by DUTC were built in the Spa Road Works in Inchicore. This factory was also later used to build buses until its closure in 1977.

The last new type of tram car released was in 1931, the so-called “Luxury” cars, which came with fully cushioned seats, a streamlined exterior, and a smoother drive.

The Changing Landscape after the Wars

Once the Civil War ended, the tram network could start repairing the damage to try to operate normally again. At that point though it had almost ten years of interrupted service and development. While there were improvements made to the network, some routes were suspended or offered limited service, and no new lines had been opened since 1913 even though the city continued to expand outwards.

At the same time the car became far more viable as a mode of transport. In 1909 the tax funded Road Board was set up to improve roads throughout Ireland. Cars themselves became easier to use, more reliable, more comfortable, and cheaper. And, bucking the trend of the rest of the country during the wars, the population of Dublin grew and continued to spread out.

This opened the door for independent companies to open their own bus lines to areas not covered by the tram network, and expand from there. Compared to a tram line, setting up a new bus route was relatively easy, much cheaper, and quicker. Some underhanded operators were even picking up passengers on tram routes by driving in front of the scheduled tram. A lot of them also used the old “hail everywhere” system to pick up passengers and often didn’t stick to a specific route, gaining them the moniker “Pirate Buses”

“The pirate buses used to go around to all different routes. Oh, they could go anywhere they liked. They weren’t confined to one route – a free-for-all! There was no bus stops, anybody could just put up their hand and stop you anywhere. Oh, they’d cut one another’s throats.”

George Doran in Dublin Street Life and Lore, Kevin C. Kearns

The appearance of buses effectively stopped the extension of the tram network further out into the suburbs, even though plans still existed to do this well into the 1930s. Even the DUTC themselves realised the advantages of the bus and applied for a licence to run buses in 1925. Their first route was between Eden Quay and Killester – a route that was already ran by another company called the Contemptible Bus Company – which has an interesting background story in its own right. This trend continued and all new routes opened or extended by DUTC were bus routes, often competing directly with smaller or larger independent operators. Originally the idea was that as a bus route became more popular, it would be converted into a tram line, but that never happened.

As happened with all the different tram companies, eventually all independent bus companies in Dublin were also merged into the DUTC and it was granted sole rights to provide public transport in the city in 1934, combining both the tram and bus network into one company.

The DUTC’s Spa Road Works stopped building new trams and started building their own buses in 1937. Buses continued to be built there until the factory was closed in 1977.

The Final Years

As the buses kept outcompeting the tram lines, even existing lines came under threat. Some lines were closed in the late 20s and early 30s, but the big nail in the coffin for the trams was the decision by DUTC to replace all tram services with buses in 1937. After that, it rapidly converted almost all its tram routes to bus routes, finalising this conversion with the tram line to Howth, which closed down on the 31st of March, 1941.

At that point only three routes remained: a tram to Dartry, the very first tram line to Terenure, and the first electrical tram line to Dalkey. The first two were closed in 1948 and the final tram to Dalkey limped into the Blackrock depot on the 10th of July, 1949, having been picked clean by souvenir hunters on its final journey despite a Garda escort.

There was still a small tourist tram line running from Sutton to Howth summit until 1959, but once that was taken over by CIE, the successor of DUTC, it quickly closed down as well. You can find out more about that line, the Lucan tram, and the Blessington tramline in the extra instalment in this series in one of the other stories on this site.

Sources:

- Lecture by Michael Corcoran, at Dublin City Library and Archive on 23 January 2007.

- “Dublin Trams 1872-1959” by Francis J. Murphy, Dublin Historical Record, Vol. 33, No. 1 (Dec., 1979), pp. 2-9

- “‘Galleons of the Streets’: Irish Trams“; History Ireland, Issue 2 (summer 1997), volume 5

- The National Transport Museum website

- “Wonders and Curiosities of the Railway” by William Sloane Kennedy, 1884

- “From Horse Drawn Trams to LUAS: A Look at Public Transport in Dublin from the 1870’s to the Present Time“ by James Scannell in Dublin Historical Record, Vol. 59, No. 1 (Spring, 2006), pp. 5-18 (14 pages)

- Dublin United Tramways article on Tramway Systems of the British Isles

Image Sources:

- Tram route map – Unknown source via Wikipedia. A larger version is available on the Wikimedia Commons.

- Tram symbols – National Archives via Wikipedia. A larger version is available on the Wikimedia Commons.

- The Standard DUTC 253 – National Transport Museum, Howth.

- Luxury Tram Cars in the Spa Works – Old Dublin Town website.

- Four trams in Cabra Depot – National Library of Ireland Flickr collection.